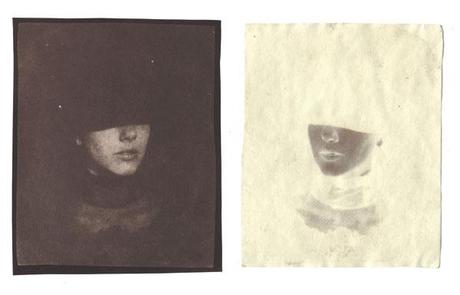

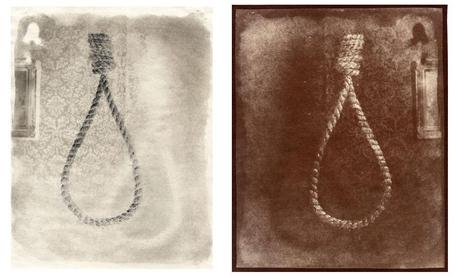

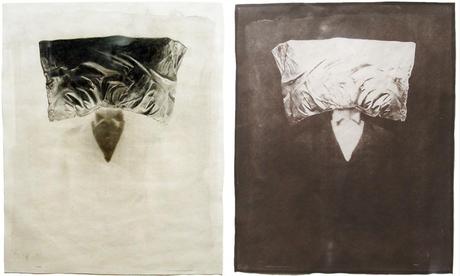

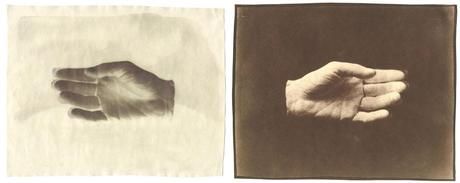

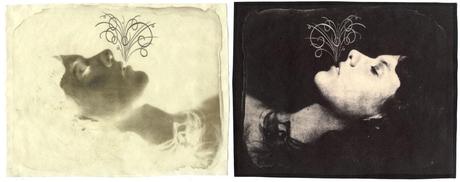

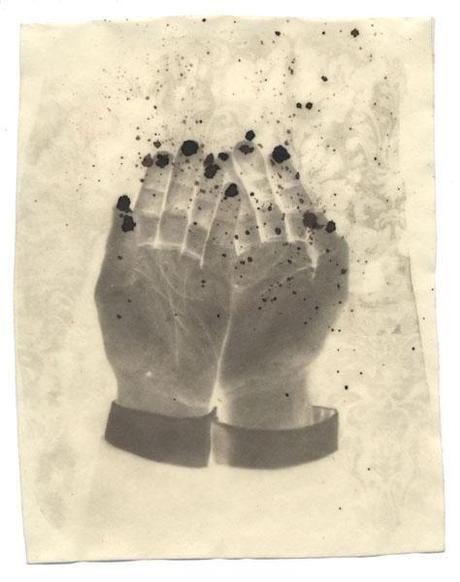

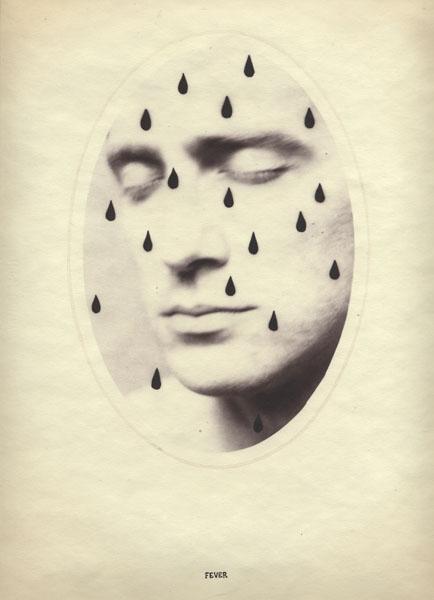

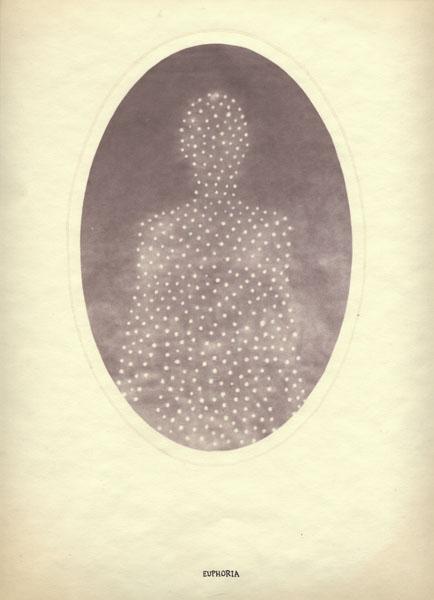

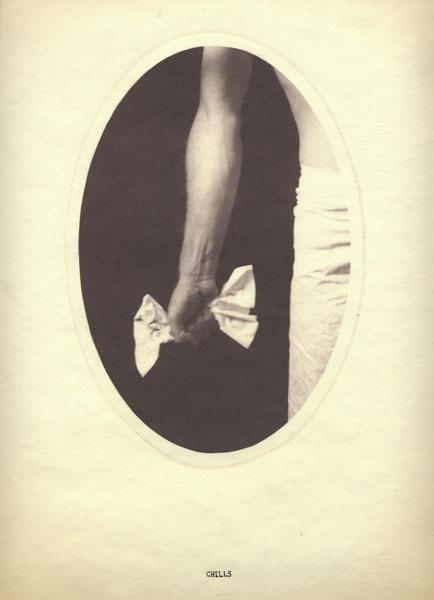

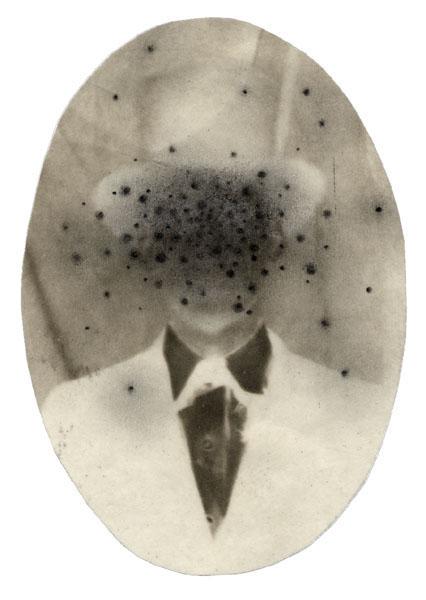

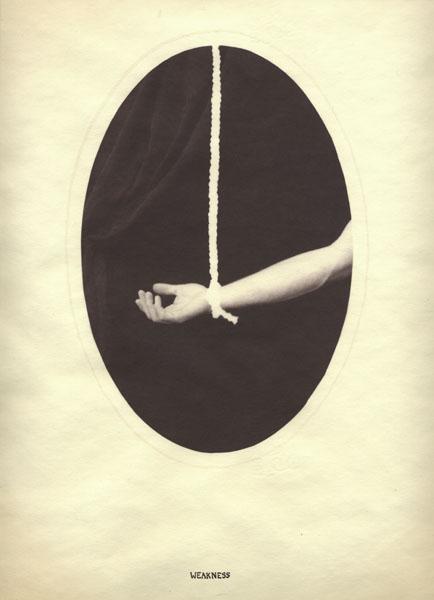

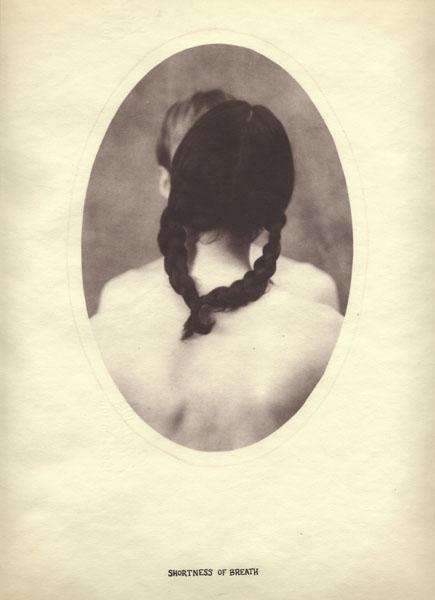

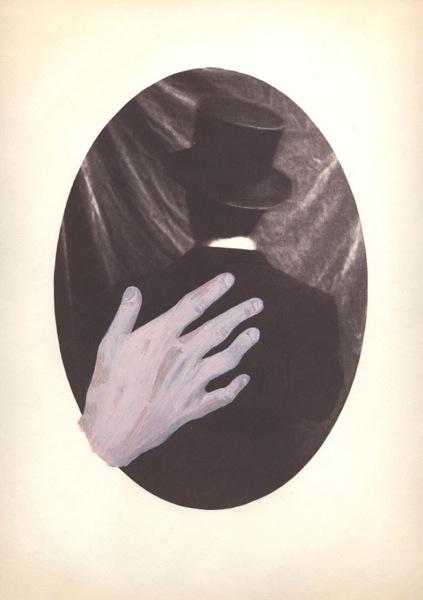

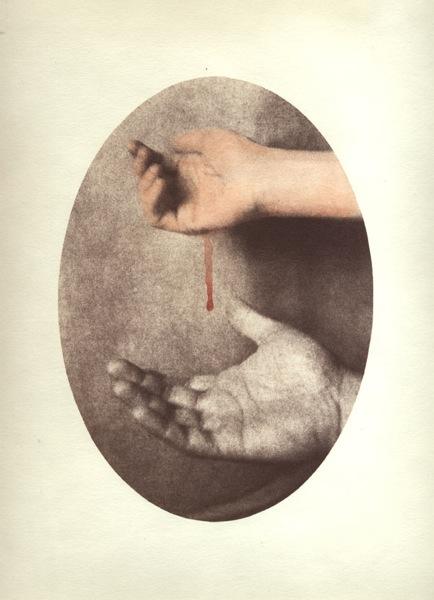

For over twenty years Dan Estabrook has been making contemporary art using a variety of 19th-century photographic techniques. Recently he has focused on the earliest paper photographs – calotype negatives and salted paper prints – as sources for hand manipulation with paint and pencil.

Dan Estabrook produces unique and deeply touching photographs – bearing a peculiar fragility, beauty and darkness.

Enjoy the interview with this inspiring artist!

SM: Your recent photography is made with techniques from the 19th century such as calotype negatives and salted paper prints. What fascinates you about these ancient photographic techniques and how did you learn them?

DE: I started working with these old processes at Harvard University, studying with Christopher James, and to be honest up until that time I wasn’t very interested in photography at all. I had always drawn and painted, and I considered art as something with which to get your hands dirty. But when I found out I could make photographs by hand – using paints and raw chemistry and fine art papers – I was hooked. Since then I’ve studied quite a few other early processes, and have developed a way of working that allows me to do everything I want: sculpture, painting, photography, drawing and so on. Working with all these materials is like a kind of alchemy for me.

SM: Your aesthetics seem to be influenced by victorian topoi but inherit surrealist elements as well. How have these epochs an impact on your work? How would you decribe your aesthetics?

DE: Well the more I worked with nineteenth-century processes, the less avoidable that era became. Certainly, from the beginning I was fascinated with all the little old tintypes and things I’d collected from flea markets and junk shops, although it took me some time to make the connections between my own work with historical techniques and the origins of photography. What I love most is how those old photographs look to us now, in the present, all faded and broken and unmoored from their original context. I started to make what I thought of as my own “found photographs”, using old processes and old styles, not in an attempt to recreate the Victorian age but to invent things that could perhaps have been lost along the way – things that now say more about our fantasies of the past than about some actual experience of that time.

As for the Surrealists, I guess I have to admit some affinity with their sexual obsessions as well as their fascination with psychology and dreams, although I’m much more interested in a kind of “accidental surrealism” than with the house brand, as it were. I love how things become strange and uncanny through the passage of time, the way a once brightly-colored hand-painted photograph might fade over the years into something ghostly and grotesque. I love all that broken-ness and decay, and I imagine secrets and messages revealed through the passage of time, even if they’re just things I’ve invented.

SM: Which themes do you treat in your photographs? Where lays their contemporary reference?

DE: Of course, it’s impossible to talk about the passage of time without talking about death, so there seems to be a morbid tone to a lot of what I do. However the sense of loss – through death, through time – that I am invoking is more about relationships and interpersonal communication than about physical death. Photographs are so much like bodies to me, seeming to keep within them some soul or aspect of the person depicted. They age as we age; their skin can crack and wrinkle too. What’s more, they forget, keeping only a glimpse of a moment – some details of the place depicted, the clothing worn, the time of day – while losing the context, the entirety of the experience. I make photographs specifically drawn from my own life that I hope speak to these universal themes – an attempt to hold onto the important things in our life while they are drawn under the current of passing time.

Frankly, I think this is an extremely contemporary experience, and much more than, say, chasing after whatever new digital technology promises more access to the world around us. How old-fashioned does that technology become in ten years? In five? The only thing that increases with every year is our distance from the past, and how hard it is to hold onto what is lost.

SM: Some of your photographs have the character of portraits. But at the same time an aura of anonymity surrounds your protagonists – as if their portrait transported rather a superior thought than their individuality. What mean portraits in your work?

DE: I am courting a kind of anonymous feeling, that’s for sure. I want one’s very first impression of a piece of mine to be feeling slightly unsure as to when it was made. However, with only a few exceptions, every person I photographed is someone with whom I have a close or intimate relationship, and even if I had intended something different, the image always ends up being about that person, that connection. It’s definitely a kind of game I play, making these seemingly anonymous photographs of archetypes – Man, Woman, Photographer, Model – that I hope do capture a more universal sense of the figure. But the images would be meaningless to me and, I think, less successful to others if they didn’t have a strong connection to a real person and a real relationship. I’ve always felt the best work comes from a purely subjective truth, and that chasing after grand themes without some firsthand knowledge is pointless. These are portraits of my friends and my loves and myself, but because they come from an honest experience I hope that other people can relate just as personally, no matter how much I try to hide.

SM: What would you name as your major influences?

DE: The early photographers are, of course, often on my mind, especially people like Hippolyte Bayard, who had all the genius and fortitude to help invent photography but suffered under a lack of support and fame. This seems like a very contemporary (and cliché) idea of the artist’s life that I can’t help but relate to. Today, there are very few photographers I admire, except for Sally Mann and Saul Fletcher, for instance. I am more often inspired by painting and drawing and sculpture – Michaël Borremans, Kara Walker, Doris Salcedo, Jeanne Silverthorne, Kiki Smith, Robert Gober, Cornelia Parker, and on and on. I could stare at beautiful things for days.

Thank you for the interview!

Dan Estabrook lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook

© Dan Estabrook